The Landscape of Online Engineering Education

This post was written to complete the final project requirement for the Winter 2020 offering of ECI289C: Engineering Planning taught by Dr. Colleen Bronner.

In engineering courses across the country, more and more interactions between instructors and students are happening in virtual space. Platforms like Canvas, Piazza, and Slack facilitate distribution of course materials, discussion among course stakeholders, and delivery of assessments to students. Some professors and teachers offer digital office hours via video conferencing tools (e.g., Zoom, Skype, Google Hangouts).

Given our reliance on online tools for conducting courses, I began to wonder, “Why can’t I earn my engineering degree without ever setting foot in a classroom?” Offering such online programs could have at least two major benefits:

- Increase accessibility to engineering education - As of Q3 of 2019, the sum total of outstanding student loans in the United States was $1.5 trillion. Imagine if a student could get an engineering degree from a top accredited program from the comfort of home. In theory, providers of remote learning could funnel funds which typically go into overhead costs (i.e., departmental facilities, dormitories, and dining halls) into crafting better content which can be delivered to a wide audience.

- Make our educational networks more robust - At the time of writing, 135 U.S. colleges have cancelled in-person classes due to the coronavirus pandemic. Here at UC Davis, many faculty are scrambling to figure out how to transition to online platforms for administering final exams. Online degree programs offer an educational environment that could proceed uninhibited by similar Black Swan events.

Assuming a purely online degree program could make good on the promise of delivering accessible and robust engineering education, that could be a major disruption to the education industry.

In recent years, organizations in both academia and industry have established platforms for online engineering education. There are at least three categories which I would bin these efforts into:

- Open Education Resources

- Online Certification Programs

- Online Degree Programs

This post investigates the viability of these different platform categories by attempting to answer the following questions for each:

- How effective are online platforms for engineering education?

- Do these online platforms offer accredited degrees in engineering?

- Do these platforms make for more accessible educational experiences?

Let’s address effectiveness, accreditation, and accessibility before describing online learning platforms.

Effectiveness: To the Research!

The definition of effectiveness means different things to different people, as outlined by Jenkins [9] with the Community College Research Center (CCRC), who distinguishes institutional effectiveness from instructional effectiveness. The former emphasizes student retention and course completion while the latter focuses on student learning.

In Online Engineering Education: Learning Anywhere, Anytime [1], researchers from the Online Learning Consortium (OLC; formerly the Sloan Consortium) highlighted some research findings on the instructional effectiveness of internet-based engineering education, including:

- “…no significant difference in learning outcomes for online and on-campus students as measured by test scores… reported over the last decade in the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks (JALN).”

- Self-directed learning approaches (called constructivist learning [2]) work well online.

Xu and Jaggars [8] with the CCRC investigated the performance discrepancies between students enrolled in online and hybrid courses; the authors reported problematic aspects associated with Washington State’s online program (WashingtonOnline), namely,

…students who took online coursework in early terms were slightly but significantly less likely to return to school in subsequent terms, and students who took a higher proportion of credits online were slightly but significantly less likely to attain an educational award or transfer to a four-year institution.

The authors cite a few reasons for this attrition, including technical difficulties, a sense of social distance/isolation, and limited online student support services, and they recommend expansion of dedicated online support services as well as faculty training in online pedagogy.

The upshot: online engineering education can be instructionally effective if instructors are designing their courses and if the administration takes a hands-on approach in supporting students.

Accreditation: What is it Good For?

For the remainder of this post, I will discuss whether or not a given platform offers an accredited degree. Accreditation is a process where a degree program submits itself voluntarily to review by an independent evaluation by a board of experts [3]. In engineering education, the major body that administers these reviews is the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (known as ABET).

The OLC paper [1] also touches on how online instuction methods can bolster the student competencies listed in General Criterion 3 for ABET accreditation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ABET student outcomes (as per General Criterion 3) and potential value added by online methods.

Accreditation is important since, in theory, it shows proof of quality. The ABET criteria all emphasize student outcomes, i.e. instructional effectiveness in engineering programs. In this way, effectiveness and accreditation have some amount of tacit synergy.

Accessibility: The Barriers to Education

The financial barriers to attaining advanced degrees are outpacing our ability to earn capital to overcome those barriers. Since the 1980’s, tuition for university degrees have increased at 8 times as quickly as wages. For this reason, I choose to focus on financial accessibility for this post, as I believe that on average, online programs can help us break down the cost barrier.

However, I do not believe that cheaper programs will be the only factor in making engineering education more accessible. For one thing, socioeconomic status effects learners earlier than the point of university enrollment. For example, K-12 students from low-income households who lack access to reliable internet access and computers perform less well than their wealthier counterparts.

Furthermore, lack of representation can make the engineering disciplines unwelcoming to prospective entrants. According to the NSF’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, women earned 20.9% of all engineering degrees awarded in 2016 and 50.9% of those degree recipients were white. Encouraging diversity, equity, and inclusion in engineering might serve to make engineering more accessible to underrepresented minorities.

The representation barrier to accessibility is salient, and I think online engineering education might be able to address it (more on that in the Coda). For the time being, I restrict my attention to financial accessibility.

Now, let’s focus in on the respective online learning platforms.

Open Education Resources (OERs)

Open education resources aggregate different learning objects and make them publicly available free of charge under an open license. One prevalent example of an OER is MIT’s OpenCourseWare (OCW), which hosts lectures, course notes, problem sets, and exams from previous offerings of actual MIT courses under the Creative Commons License. Video 1 is the fully recorded first lecture from the excellent Linear Algebra course on OCW.

Video 1: Online recording of Lecture 1 of the Fall 2011 offering of 18.06 Linear Algebra with Gilbert Strang.

The criterion of accreditation does not really apply here, as OERs are not in themselves degree-offering programs. So we can focus on effectiveness and accessibility.

Effectiveness: The research into effectiveness of OERs in student outcomes has been middling, and Grimaldi et. al [4] discuss some of the reasons why. The former, open education resources could serve to bolster in-person teaching and learning, as instructors might include them in “Additional Readings” sections in their syllabi.

Accessibility: The case for accessibility of OERs is self-evident; by publishing a large body of freely available learning objects. However, this presumes that all students have access to decent computers and internet connections, which is likely correlated with socioeconomic status (i.e., students from wealthier backgrounds have better technology available than students from less wealthy backgrounds).

Furthermore, merely distributing course materials does not offer the same educational experience that one has in a university classroom. Marc Clarà [5] grounds this notion in developmental psychology through his discussion of Vygotsky’s theory of the “Zone of Proximal Development,” arguing

…conceptual development is driven only by instruction that promotes the [learner’s] formation of nonspontaneous meaning.

(Here, nonspontaneous meaning can be taken to mean scientific or mathematical concept.) We can see that on their own, OERs might fall short in both the departments of effectiveness and accessibility. A database of resources does not give an individual learner access to peers and instructors who enable them to grasp difficult concepts, reducing the ultimate instructional effectiveness of these platforms.

Online Certification Programs

Whereas OERs merely provide materials to students, Online Certification Programs (OCPs) involve interaction between the provider of educational materials and the learners. Furthermore, they offer certifications to those who complete the courses. For example, Udacity is offers paid programs on a range of tech-related topics (e.g., AI, Data Science, and Entrepreneurship).

While OERs often take materials and lectures from in-person classes and merely post them online, the materials for OCPs are often built with online learning environments in mind. Below, Video 2 highlights an example of a learning object from a Udacity course.

Video 2: An online module from CS344: Intro to Parallel Programming with John Owens (UC Davis).

Effectiveness: From an effectiveness standpoint, there is not a wealth of published research on OCPs. I suspect most researchers of engineering education design and carry out their experiments in own respective classrooms, and the set of the instructors of OCPs must not overlap substantially with the set of engineering education researchers. OCPs self-report on the efficacy of their programs by touting the promotions and jobs which their participants secure (e.g., Figure 2).

Accreditation: OCPs like Udacity typically do not offer accredited degrees. OCPs target market appears to be professionals who want to develop practical, career-oriented skills within their competencies or who want to make a career transition. Indeed, OCPs like eCornell offer programs, such as “Engineering Leadership” which comes with an “Engineering Leadership Certificate” as well as Professional Development Hours (see Figure 3).

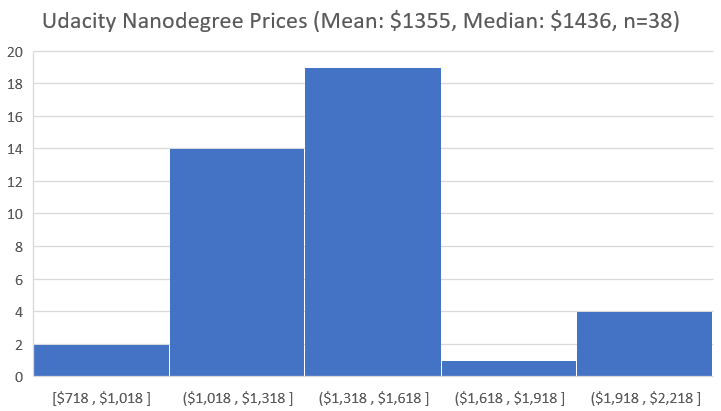

Accessibility: From an financial accessibility standpoint, these programs have a range of price tags. For example, the average cost of a Udacity “Nanodegree” program is about $1355 (Figure 4). For an established professional with a steady income, this might be affordable, but for less economically advantaged individuals, this might be out of the question. As a another OCP alternative, Coursera offers “specialization programs” which range from $156-$474 total cost (based on monthly rate estimates available here).

Online Degree Programs

Finally, let’s consider fully accredited online degree programs (ODPs). Many well-established public (e.g., Ohio State) and private (e.g., Columbia) institutions offer ODPs in engineering.

Effectiveness: Here, I will refer to the initial discussion on effectiveness. These ODPs can be just as instructionally effective as in-person programs provided that instructors consider the unique challenges of online pedagogy and that administration implements strong online support systems for the enrollees [8].

Accreditation: With respect to online engineering degrees, the emphasis appears to be on Master’s degrees. U.S. News publishes a list of “Best Online Master’s in Engineering Programs,” and a search on the 2020 list filtered for “100% Online” returns 76 schools, of which 57 are public universities, 18 are private, and 1 is for-profit. A similar search for “Best Online Bachelor’s Programs” with the “Engineering, General” filter returns only 5 schools (4 public, 1 private). Another site,bestdegreeprograms.org, claims to have a list of the 25 best online engineering bachelor’s programs which they claim to have winnowed down from 85 programs, but they do not produce this full list.

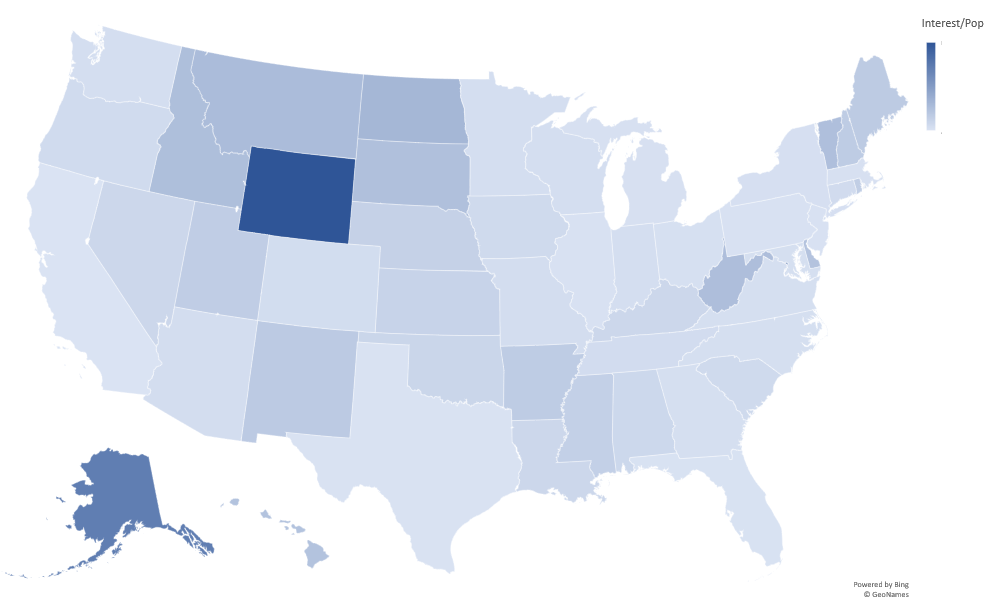

Accessibility: From an accessibility perspective, ODPs might offer a means for folks living far from population centers to get a solid engineering education (see Figure 5 for some first-order support for this claim).

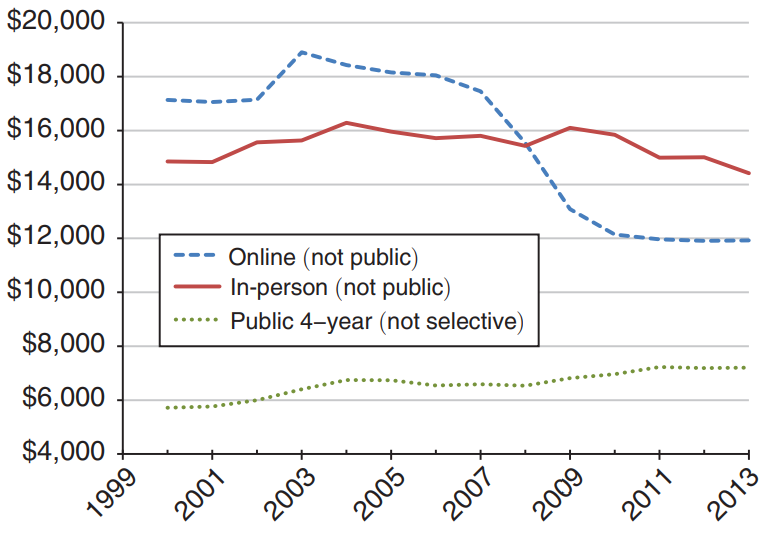

Deming. et al discuss financial accessibility of ODPs [6]; the 2015 paper claims that schools which are predominantly “Online” have tuition costs which are trending downward, which contrasts with in-person schools whose tuition costs have leveled off on average (Figure 6).

Furthermore, Goodman et. al [7] demonstrate that an online computer engineering master’s degree option at the Georgia Tech provides access to seekers of education from older demographics, writing

Our causal evidence shows that this online option expands access to education and does not substitute for other informal training… This is the first rigorous evidence that we know of showing that an online degree program can increase educational attainment, implying that the higher education market had previously been failing to meet demand for this particular bundle of program characteristics.

Coda: Bricks vs. Bits

The premise of this post was to answer the question: “Why can’t I earn my engineering degree without ever setting foot in a classroom?” I described three types of online engineering platforms, open education resources (OERs), online certification programs (OCPs), and online degree programs (ODPs), which answer this question with “no,” “kind of (but no),” and “yes,” respectively. Broadly speaking, all of these mechanisms serve to increase accessibility with respect to age, geographic location, and financial cost. Given their distributed nature, these online avenues also make our educational systems more robust to external shocks.

However, which I have skirted around a follow-up question: “What is an engineering education for?” In the way that I answered the “effectiveness” question, one might take the ABET criteria as the gospel of educational outcomes for newly minted engineers.

But going to university is not all about gaining technical skills, which (as discussed in this post) can be done online. Tyler Cowen and Jordan Peterson discuss some of these intangible benefits for leaving home and attending an in-person program,

[U]niversities give young people a four-year, socially sanctioned identity that they can adopt while they’re experimenting and trying to mature… Universities give students, young people something to do when they leave home first while they grow up… Universities give people a chance to reconstitute their peer network and emerge as different people. Universities give people a chance to contend with the great thought of the past… To find mentors, to become disciplined, to work towards a single goal. And almost none of that has to do with content provision. - Jordan Peterson

I think if online engineering education is to take off in any meaningful way, educators need to figure out how to provide these intangibles. Programs like the Minerva Schools are examples of what institutions might do to marry a distributed, online educational model with global cultural immersion.

With regards to accessibility, Minerva might circumvent mere financial barriers and make education more broadly accessible; the school boasts an admissions process which “eliminates unfair biases,” by eliminating evaluation of standardized tests (e.g., SAT, ACT), gender/ethnicity, financial status, or legacy status.

Some engineering disciplines face distinct challenges in making such progressive online programs work, and if we hope to make engineering education effective, accessible, and robust while still exposing young adults to a diversity of worldviews, then we must make them work.

References

- [1] J. Bourne, D. Harris, and F. Mayadas, “Online Engineering Education: Learning Anywhere, Anytime,” Online Learn., vol. 9, no. 1, 2019.

- [2] S. Gold, “A constructivist approach to online training for online teachers,” J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 35–57, 2001.

- [3] S. I. Gerasimov and S. O. Shaposhnikov, “Basic Principles of Public-Professional Accreditation of Educational Programs.”

- [4] P.J. Grimaldi, C. B. Mallick, A.E. Waters, R.G. Baraniuk, “Do open educational resources improve student learning? Implications of the access hypothesis.” PLOS ONE 14(3): e0212508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212508. 2019.

- [5] M. Clarà, “How Instruction Influences Conceptual Development: Vygotsky’s Theory Revisited,” Educational Psychologist, 52:1, 50-62, DOI: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1221765. 2017.

- [6] D.J. Deming, C. Goldin, L.F. Katz, and N. Yuchtman, “Can Online Learning Bend the Higher Education Cost Curve?” American Economic Review, 105 (5): 496-501. 2015.

- [7] J. Goodman, J. Melkers, and A. Pallais. “Can Online Delivery Increase Access to Education?” Journal of Labor Economics 2019 37:1, 1-34, 2019.

- [8] D. Xu and S. Jaggars. “Online and hybrid course enrollment and performance in Washington State community and technical colleges.” 2011. https://doi.org/10.7916/D8862QJ6

- [9] D. Jenkins. Redesigning community colleges for completion: Lessons from research on high performance organizations (CCRC Working Paper No. 24, Assessment of Evidence Series). New York, NY: Columbia University, Teachers College, Community College Research Center. 2011.